Colonial Representations of Pasifika Culture, Fear of the cannibal and Staged Authenticity

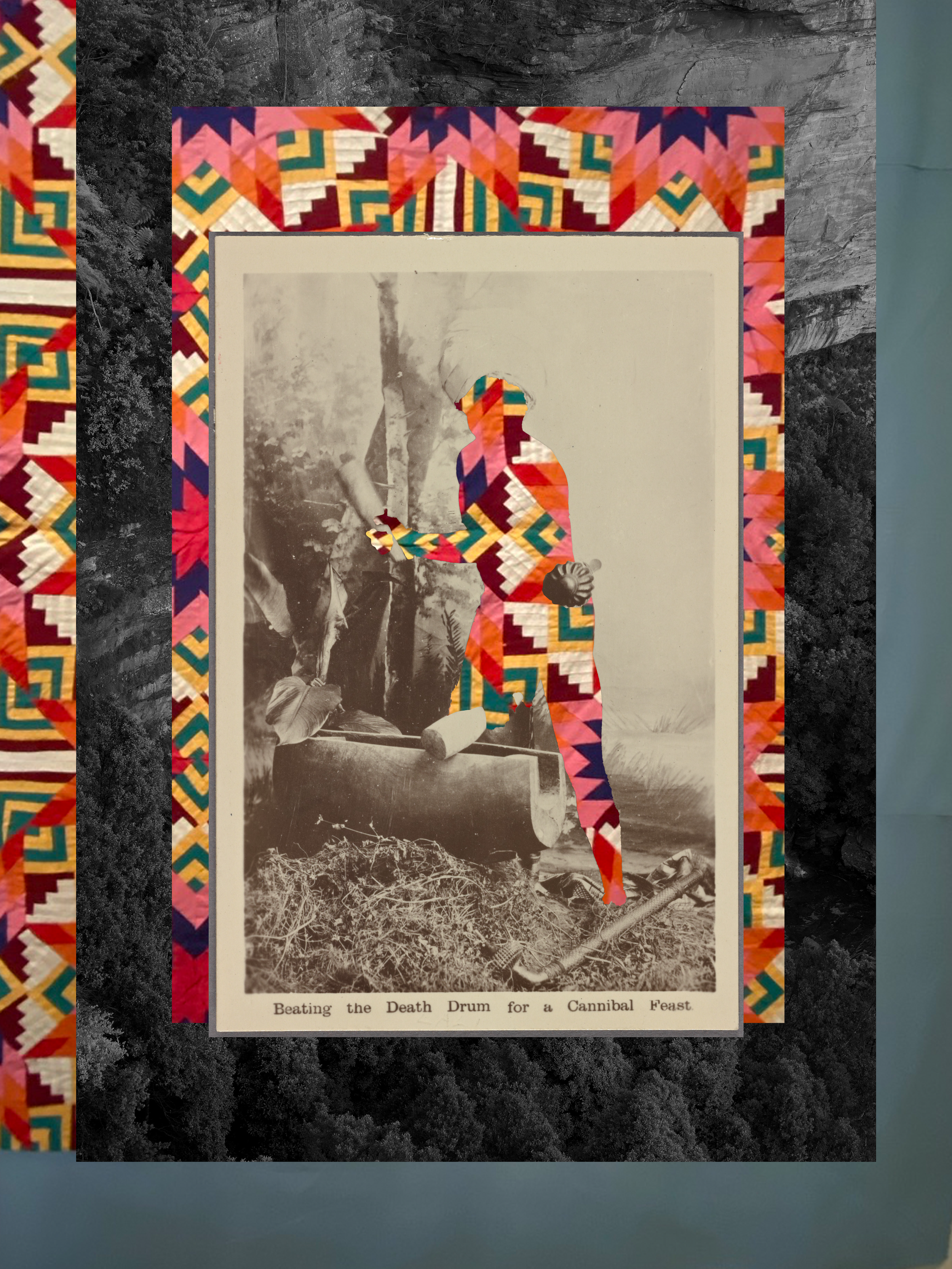

Beating the Death Drum

This is my resent experimentation collage. The postcard I used is one of a series or collection of Fijian postcards displaying performed ethnicity, in this case perpetuating the fear of the Fijian cannibal.

The fear of the savage cannibal was used as a tool by colonial powers, presenting the qualities of the native or savage as innate, to which only colonisation could be the solution for. Justifying colonial power.

‘European narratives about cannibalistic activities among cultural others, regardless of the authenticity of such claims, were used to justify what amounted to very real acts of violence, and sometimes genocide, on the part of the West’ Flexner and Taki

In this work I team this staged representation of culture, with a learned colonial craft that Pasifika people have made their own. Representing iconic imagery like the breadfruit, hibiscus and the colour and vibrancy of their surrounding environment.

In this postcard labeled ‘Beating the Death Drum for a Cannibal Feast’ there is a Fijian man in a staged scene beating a ‘death drum’, he is actually beating a Lali, which was used by members of the village as a communication tool, signifying a possible attack, notifying a gathering, with smaller versions even being used in Meke as an instrument. So much in these postcards is not accurate but we know this is not the point of them, they were not made to accurately represent culture. They were highly staged pieces of propaganda used to justify the colonial project in the Pacific.

‘This perception was constructed based on historical experience in which instances of violence against Europeans were given a disproportionate place in the colonizer’s imagination. Black magic, cannibal feasts, and general chaos and terror were supposed to be the elements of Melanesian social life. This couldn’t be further from the truth of lived experience in traditional societies in islands like Erromango (Naupa, 2011). Nonetheless it provided a compelling narrative that colored colonial perceptions, especially for missionary audiences (American Sunday School Union, 1844; Gordon, 1863; Robertson, 1902).’

The links to the below articles are so interesting and worth reading:

Fear of a cannibal island: Colonial fear, everyday life, and event landscapes in the Erromango missions of Vanuatu James L Flexner and Jerry Taki

Cannibals and colonizers

European conceptions of cannibalism were projected into the deep past, or into the exotic, faraway places of the present. Claims of cannibalism among cultural others were usually accepted without critical analysis, while claims about anthropophagy among recent Westerners are dismissed out of hand as unique instances of individual deviance or desperation (Arens, 1980; Barker et al., 1998; Goldman, 1999; Obeyesekere, 2005). European narratives about cannibalistic activities among cultural others, regardless of the authenticity of such claims, were used to justify what amounted to very real acts of violence, and sometimes genocide, on the part of the West. The Tupinamba, a Brazilian Indigenous group, were characterized as a “cannibal tribe” in 16th-century colonial literature. A combination of demographic upheaval and colonial violence would forever change the nature of Tupinamba life, meaning it is not possible to know whether this claim was based on observation or myth. “Although there may be some legitimate reservations about who ate whom, there can be none on the question of who exterminated whom” (Arens, 1980: 31). In the South Pacific, there was likewise a tendency to emphasize the cannibalism of Islanders as a way of legitimizing the violence of the colonial endeavor (Obeyesekere, 2005). In contrast, a few very well-documented instances of cannibalism among Westerners, including some attested to by clear archaeological evidence (e.g. Dixon et al., 2011), have been treated as historically aberrant and not at all representative of Western societies.

While there are many problems with interpreting claims of cannibalism in historical and anthropological literature, for the purposes of the analysis here, it is not important whether a particular act of anthropophagy actually occurred. Rather than attempting to determine which colonial fears were justified, the goal is to understand fear and anxiety in the colonial experience as a reflection of the problematic, inconsistent, ambiguous relationship between narratives, behaviors, and material conditions (Hall, 2000). While avoiding casting Melanesian people as passive victims of colonial history, we acknowledge the role that violence of various sorts played in the creation of the colonial order (see González-Ruibal and Moshenska, 2015; Todorov, 1984). Colonial violence was nonetheless interpreted in Melanesian terms, and Melanesian people acted according to their own worldviews and morality, including by defending their islands with violent acts of their own. We demonstrate the ways that danger and violence, whether real or imagined, played on, and continue to play on European and Melanesian people’s imaginations, using examples from Erromango’s archaeological landscapes of fear.

This quote by Rev. Joseph Copeland, which was meant to characterize the nature of Indigenous life in the New Hebrides in general, provides a useful encapsulation of the ways that Westerners perceived Melanesian Islanders. This perception was constructed based on historical experience in which instances of violence against Europeans were given a disproportionate place in the colonizer’s imagination. Black magic, cannibal feasts, and general chaos and terror were supposed to be the elements of Melanesian social life. This couldn’t be further from the truth of lived experience in traditional societies in islands like Erromango (Naupa, 2011). Nonetheless it provided a compelling narrative that colored colonial perceptions, especially for missionary audiences (American Sunday School Union, 1844; Gordon, 1863; Robertson, 1902).

Local social memories contain detailed, place-based information about missionary deaths in Erromango. The landscapes in which missionaries were killed at Dillon’s Bay are not only remembered, but experienced and in some ways performed locally. Elders and knowledge keepers will show young people or visitors where John Williams fell, or where George Gordon fled in trying to escape his attackers. This is reminiscent of what cultural geographers call the “haunted” or “spectral” aspects of social memory as it is experienced in place (e.g. McCormack, 2010; Wylie, 2007). Memories on Erromango construct what Flexner (2014b: 7) terms “event landscapes”, places where specific past happenings are manifested, remembered, and performed in the present.

Ongoing colonial contacts on Erromango resulted in violence and venereal disease, especially from the sandalwood trade, which harvested the fragrant wood used to make incense and other valuables (Shineberg, 1967: 90–91). According to one account following the discovery of sandalwood on Erromango in 1825, over £175,000 (an enormous amount of wealth in 19th-century value) worth of the valuable timber was removed in less than 50 years, at no apparent benefit to the local population (Robertson, 1902: 34). Oral traditions record regular bouts of violence with sandalwood cutters in and around Dillon’s Bay (Naupa, 2011: 78–86). Population reduction from disease combined with the removal of hundreds of local people for the labor trade, usually but not always young men. Again, Erromangan traditions recall the trauma caused by “blackbirding” (Naupa, 2011: 86–92). In some cases people were tricked and essentially sold into indentured servitude in Fiji and Queensland (Australia), though it appears that many people also chose to go to the plantations (Docker, 1970; Moore, 1992; Palmer, 1871; Shineberg, 1999). Melanesian people died in unprecedented numbers over the course of the 19th century as Europeans, including missionaries, settled in their islands (McArthur, 1981; Spriggs, 2007). The missionaries’ god appeared to be powerful as well as vengeful, while the ability of the local spirits and magic to resist them appeared less and less effective (Flexner, 2016: 5, 160).

Colonial Spectacle, Staged Authenticity and Other Heritage Paradoxes on a Fijian Island

The intention is to distinguish realism as achieved in their tourism performance from authenticity, which we see not much as a symptom of a doubt but a problem of authentication—who has the power to determinate what will count as authentic? Said (1978), Foucault (1980), Appadurai (1986), Marcus and Myers (1995), Trask (1993), and others suggest that the power to represent or to consume other cultures is a form of “domination.” In my paper, however, I employ the concept of cultural cannibalization, a western ideological device, a colonial tool, and a particular tourist gaze to consume, and to represent for popular consumption, the alien Other in Fiji and Oceania in general.